With the Russo-Ukrainian War now rolling on into its seventh month, I thought this might be as good a time as any to put together a more extensive analysis than the twitter format allows. What follows will be my assessment of what exactly the Russian Armed Forces have achieved, why they made specific operational choices, and the general shape of the battlefield today.

But first, I will indulge in a brief paragraph about myself. Feel free to skip this and proceed to the first section heading below.

I am a luddite by nature and have never had any sort of social media presence. However, when the Russo-Ukrainian War began in February, I was alarmed by the amateurish, even clownish levels of analysis that were being amplified by the typical establishment channels. Public figures that contravened the collective wisdom, like Colonel Douglas MacGregor or Scott Ritter, were largely ignored. It seemed to me that the public was being memed into believing a story about cartoonish Russian incompetence, while what I saw was a lethal and locked-in Russian military waging an intelligent war. I will freely confess to having Russophilic tendencies, like many American Orthodox Christians. However, I will also bluntly say that when you’ve read as much military history as I have, you begin to see things a certain way – perhaps this is bragging, but I don’t think so. I don’t claim to be smarter than anybody else; I did spend the last fifteen years extensively reading in subjects that gave me a strong base of knowledge for the current moment, but it seems to me that I simply got lucky picking a hobby that would one day be so relevant.

So, I created a twitter account hoping to contribute to the discussion however I could, as well as to capitalize on the current fascination with war to talk about military history. People seem to like it, so I’ll try to keep doing it.

Now, let’s talk about the war. A great deal has been said, and will be said, about the causes of the war and Russia’s motives and aims in Ukraine, but I would like to skip this and proceed directly to discussing the operation itself.

How I Think About War

We should begin by acknowledging that the Russo-Ukrainian War is a novel experience for humankind. This is the first high intensity war between peer states to occur in the social media age. The content and pace of the information hitting the internet has therefore from the first moment been an aspect of the conflict itself. Ukraine, which is almost entirely dependent on foreign financing, intelligence, and weaponry, has from the beginning been hard at work shaping the story of a plucky underdog showing unexpected resilience against a barbaric invader.

All the basic motifs of this story have been well established from early on, and have been continuously reinforced with an unending barrage of pictures depicting burning vehicles which we are assured are all Russian.

Ultimately, Ukraine’s ability to shape the narrative has been aided and abetted by four major facets of the information war:

- Russia has done little to contest Ukraine in the information space. Ukraine enthusiasts eagerly propagate Ukrainian claims, no matter how absurd, but the information coming from the Russian side mostly takes the form of dry briefings from the MOD. Ukraine is playing a Marvel movie, Russia is putting on a webinar.

- Russia’s operational plans are a secret. This very fact allows the Ukrainian side to interpolate their aims, putting words in Russia’s mouth, as it were. This is how we got to the claim that Russia expected Kiev to fall in three days, but more generally the inherent uncertainty in war favors the side with the more aggressive propaganda arm.

- People, to put it bluntly, don’t know anything about war. They don’t know that armies use up lots of vehicles in a high intensity conflict, and so a picture of a burning tank seems very important to them. They had never heard of MLRS before this year, so the HIMARS seems like a futuristic wonder weapon. They don’t know that ammo dumps are a very common target, so videos of big explosions seem like a turning point.

- Finally, Ukraine has enjoyed the enthusiastic collaboration of western governments, government-controlled “thinktanks” like the Institute for the Study of War, and western media.

Through the interaction of these factors, people are being barraged with information which they are not equipped to interpret, and the sheer noise has convinced most people that Ukraine is, if not winning outright, at the very least badly frustrating the Russian army and exposing Russian incompetence.

I am not interested in a pictures of scrap metal, vehicle wrecks, or flat tires. What I am interested in is the ability of armies to deliver sustained and effective firepower, and to intelligently plan and implement operations. The basic objective in war is to destroy the enemy’s fighting power – it’s not to raise a flag in the center of Kiev and it’s not to claim nominal control over empty territory. Wars are won by destroying the enemy’s ability to offer armed resistance, and my belief is the Russians are prosecuting an intelligently designed operation that has them well on course to destroy the Ukrainian Army and achieve their political objectives.

Allow me to walk you through my interpretation of the Russian operational scheme.

The Kiev Thunder Run

Nothing did more to confuse mainstream narratives than Russia’s rapid move to the environs of Kiev in the opening days of the war. This remains a jumble for most people – the Gostomel airport operation, the 40-mile (or was it 4, or 400? Nobody can remember) column of vehicles on the highway, the Ukrainians arming the general populace, then claiming that the ensuing crossfire was a Russian attempt to storm the city, and finally the Russian withdrawal. It’s a clutter of disjointed happenings, and the bedrock of the lie that will not die – the “three-day operation” meme.

I’ll tell you what I think Russia was attempting to accomplish, and what I think happened.

Let’s first dispense with the silly theory that Russia wanted to “capture” Kiev. Really, “capture” is one of those buzzwords that get thrown casually around without people really thinking about what it means. The Kiev metropolitan area is home to nearly 3.5 million people, and as the capital it is a stronghold of Ukrainian security organs. Capturing a city doesn’t just mean blasting your way to the city center; this isn’t a game of tag. Capturing means controlling, policing, countering insurgency, and asserting political control. The force that Russia brought to bear around Kiev was clearly insufficient for this task. Furthermore, in the opening phase of the war, Russian forces consistently bypassed urban areas, except for in the south and the east – more on that in a bit.

Now, it certainly seems rational to assume that the Russians harbored at least some hope that the sudden appearance of a substantial Russian forces on the doorstep would spook Kiev into surrender, or perhaps political fragmentation. That did not happen – in fact, the Ukrainian political center has largely held thanks to intensive intervention from western sponsors, who have propped up the regime with cash injections and material aid. Let’s clarify what this means though – Russia may have hoped for a very short war, but this outcome was always contingent on Ukraine lacking the political will to fight. There is no evidence that the Russian military believed they could “conquer” Ukraine in three days, three weeks, or three months. That’s a silly thing to even say.

So, what was the military rational for the move on the Kiev region? I believe that in the broadest sense the intention was to disrupt Ukrainian deployment, and that the Russian army succeeded in this objective. Let’s look at the specifics.

As I just mentioned, Russian forces in the opening phase opted to bypass urban areas, and never made meaningful attempts to enter or occupy Kiev, Kharkov, or Sumy. They did, however, enter cities in the south and the east, including Kherson, Melitoipol, Berdyansk, and of course Mariupol. The conduct of the war was radically different in the two theaters. In the north, Russian forces moved fast and hard, staying out of urban areas, and making no attempts to consolidate control of the territories they were passing through; in the south, the movements were more methodical, urban areas were cleansed, and the Russians actually deployed the administrative, humanitarian, and policing tools needed to digest and eventually annex captured territory.

It’s very obvious that in some parts of Ukraine – Donestk, Lugansk, Zaporizhia, and Kherson oblasts, the Russians came to stay, and in others – Kiev, and Sumy – they did not. Everything that occurred around Kiev should therefore be viewed in light of what happened in the south.

On the operational level, what Russia achieved with its drive on Kiev was the paralysis of Ukrainian deployment which allowed for the relatively unhindered capture of key nodes in other theaters. The early phases of Ukrainian mobilization were hectic and scattered, largely because it was unclear what the focal point of the Russian operation was. There were fears that Kharkov would be taken, that Odessa might come under amphibious assault, or that Kiev itself was about to be stormed. Zelensky even dramatically told the world that the fate of Kiev was about to be decided – but of course, the Russian army never actually tried to enter the city.

With multiple axes of advance and missile strikes all over Ukraine, the AFU were very clearly paralyzed in the opening days of the war. But the Russian presence near Kiev had one particularly important implication for Ukrainian mobilization.

People following the battles around Kiev in the first month of the war probably noticed three place names coming up regularly – Gostomel (the site of the airport operation), Irpin, and Bucha. If you aren’t familiar with Ukrainian geography, you may not realize that these three cities are all suburbs of Kiev that are directly contiguous with each other: from the northern tip of Gostomel to the southern edge of Irpin is only about seven miles. They make up one continuous urban area, and they happen to lay immediately to the north of the E40 highway, which is the main east-west arterial of Ukraine. Russian forces sat on this for most of March, blocking E40, forcing Ukraine to keep forces tied up around Kiev, and totally preventing Ukraine from contesting the capture of key objectives.

Let’s briefly talk about the Gostomel airport operation.

The narrative being spun by the Ukrainian propaganda machine is that Russian airborne units attempted to capture the Gostomel airfield so that additional units could be brought in by air for an assault on Kiev. Furthermore, they maintain that the Russian paratroopers (VDV) were annihilated. This is utter nonsense.

For starters, we should remember that just a day into the war, the Ukrainians told the world that they had destroyed the Russian airborne forces at Gostomel. Taking this claim at face value, a CNN news team actually drove out to the airport and found… VDV, in control of the perimeter. The VDV, knowing that CNN isn’t important, allowed the camera crew to hang around for a bit filming them. Yet, despite CNN broadcasting live that the Russians were in full control of the airport, people still are under the impression that they were annihilated. Very strange.

Furthermore, it is absolutely bizarre to believe that the Russians intended to take Kiev by landing forces at the airport. It was claimed that Russia had 18 IL-76 transports loaded up to deposit forces at Gostomel, but these planes would not even be sufficient to carry a single Battalion Tactical Group. So, why go for the airport?

Red Army operational doctrine classically called for targeted paratrooper assaults to be conducted at operational depths, for the purpose of paralyzing defenses and tying up their reserves. If, as I believe, the main purpose of the drive on Kiev was to block the city from the west, obstruct the E40 highway, and disrupt Ukrainian deployment, then a paratrooper assault on Gostomel makes perfect sense. By inserting forces at the airport, the VDV ensured that Ukrainian reserves would be tied up around Kiev itself. Russian ground forces needed to make a 60 mile dash south to reach their objectives in Kiev’s western suburbs, and the VDV operation at the airport prevented Ukraine from deploying forces to block that advance to the south. It worked; the VDV held the airport until they were relieved by Russian ground forces, who linked up with them on February 25. As an added bonus, they managed to destroy the airport itself, rendering Ukraine’s primary cargo airfield in the Kiev region inoperable.

During the month of March, while the world was fixated on Kiev, Russia captured the following major objectives, which collectively had huge implications for the future progress of the war:

- On March 2, Kherson surrendered, giving Russia a stable position on the west bank of the Dnieper and control of the river’s delta.

- On March 12, Volnovakha was captured, creating a secure road connection to Crimea.

- On March 17, Izyum was captured. This city is critically important, not only because it offers a position across the Severodonetsk River, but also because it interdicts the E40 highway and rail lines connecting Kharkov and Slavyansk. Izyum is always fated to be a critical node in any war for eastern Ukraine – in 1943, the Soviets and Germans threw whole armies at the narrow sector around Izyum and Barvenkovo for a reason.

- By March 28, Russian forces had pushed deep into Mariupol, breaking continuous Ukrainian resistance and setting the stage for the starving out of the Azov men in the Azovstal plant.

In other words, by the end of March the Russians had solved their potential Crimean problems by securing road and rail links to the peninsula, stabilizing the connection to Crimea with a robust land corridor. Meanwhile, the capture of Izyum and Kupyansk created the northern “shoulder” of the Donbas. They achieved all of this against relatively weak resistance (with the exception of Mariupol, where Azov fought fiercely to avoid capture and war crimes charges). The AFU would surely have loved to deny Russia the capture of the critical transit node at Izyum, but they could do little to contest the city’s capture, because the E40 highway was blocked, their forces were pinned down around Kiev and Kharkov, and their decision making was paralyzed by the octopus tentacles reaching into the country from all directions.

While all of this was going on, the Russian forces near Kiev were engaged in a series of high intensity battles with units from AFU Command North, dishing out extreme levels of punishment. A premature attempt to dislodge the Russians from Irpin was badly mauled. Russian forces were able to trade at excellent loss ratios around Kiev while serving the broader operational purpose of paralyzing Ukraine’s mobilization and deployment so that the Azov Coast and the northern shoulder of the Donbas could be secured.

It is my view that this was a fantastically successful operation that solved the logistical problem of a land bridge to Crimea while positioning the Russian armed forces well for further success in the east. Once key objectives had been achieved on other fronts, the pinning operation was no longer needed and Russian forces withdrew for rest and refitting. It is not a coincidence that the beginning of the Russian withdraw coincided with the capture of Izyum and the beginning of the endgame at Mariupol.

It’s worth noting that less than a week before Russia began its withdrawal from the Kiev suburbs, the head of the Kiev Regional Military Administration explicitly stated that no offensive actions could or would be undertaken to eject the Russian army from Bucha. Ukraine was still in a defensive stance around Kiev when the Russian withdrawal began. This was a voluntary withdrawal prompted by the completion of key objectives elsewhere in the country – it was not a retreat forced by Ukrainian counterattacks.

Summary: Russia had no intention of “storming”, “capturing”, or “encircling” Kiev. The objective of this first phase was to block Kiev from the west, in particular the E40 highway, disrupting Ukraine’s mobilization and preventing the deployment of forces to contest the capture of northern Donbas nodes (Izyum) and the land bridge to Crimea. They succeeded and inflicted serious casualties on the AFU in the process, before withdrawing due to the completion of stage 1 objectives.

The Donbas Grind

After the completion of the first operational phase, marked by the successful consolidation of a land corridor to Crimea and the capture of the northern edge of the Donbas salient, Russia enjoyed an operational pause to rest, refit, and prepare for the second phase of the war, which has focused on liberating the territories of the LNR and DNR and – above all – grinding Ukrainian manpower down.

Let’s make a brief note about the nature of the Donbas itself. This is a region that is rich in natural resources, and during the Soviet era it enjoyed substantial investment that built it up into an industrial powerhouse. As a result, this is by far the most urbanized and populated region in Ukraine. Donetsk Oblast is not only the most populous oblast in Ukraine, it’s a full 33% more populous than Dnipropetrovsk, which is next on the list. It is also by far the most densely populated oblast. This is a dense web of towns, mid-sized cities, factories, mines, and forests – not at all like the open fields that characterize Ukraine.

The urbanized nature of the Donbas necessitates an attritional, positional approach. Ukrainian forces have spent much of the last eight years turning the towns around Donetsk into fortresses – many of these towns are long devoid of civilian residents and have been transformed into concrete strongpoints. Russian operational logic has always dictated that progress through the Donbas would be slow and methodical, for a few reasons.

First and foremost, Russia is waging an economy of force operation, which means making maximally efficient use of infantry – by far the scarcest resource in the Russian arsenal. They have augmented infantry forces with Wagner Private Military Contractors, DNR and LNR forces, and Chechens, using regular Russian infantry only sparingly. Instead, they prefer to lean on their massive advantage in artillery to shred Ukrainian positions before they even consider an approach.

The most vivid description of the Russian methodology in the Donbas came from Ukrainian war reporter Yuri Butusov, who published the following description of the defense of Piski – a key fortified strongpoint near Donetsk:

“Peski. The meat grinder… As I wrote earlier, 6,500 shells on one f**king village in less than 24 hours. It’s been like this for six days now, and it’s hard to fathom how any number of our infantry remain alive in this barrage of fire…. We almost do not respond. There is no counterbattery fire at all, the enemy without any problems for himself puts artillery shells in our trenches, takes apart very strong, concrete positions in mere minutes, without a pause and minimal rest squeezing our line of defense… It’s a f**king meat grinder, where the batallion simply holds back the assault with its own bodies… huge numbers of our infantry are ground up in one day… All the reserves disperse, the military equipment goes up in flames, the enemy approaches and takes our positions without any problems after another barrage of artillery.”

Needless to say, the Ukrainians lost Peski. It is now in Russian hands. This is the process that is being repeated ad infinitum in the Donbas. Ukraine’s advantages, as such, are a tremendous edge in human resources (Ukrainian manpower probably holds at least a 4 to 1 edge over Russians) and the ability to sit in built up defenses. Russia is nullifying this with patience and a tremendous edge in all types of firepower, including tube artillery, rocketry, and air power.

The final argument by the Ukrainians, always, is that even though they are losing key positions and even important cities – Mariupol, Severdonestk, Lysychansk, and so on – the Russians are taking horrible casualties. This simply makes no sense – not to be blunt, but it’s unclear how exactly Russians are supposed to be dying in large numbers right now. Ukrainian artillery is massively outgunned, and the Ukrainian air force is nonexistent over the Donbas. The only way Russia could be taking severe casualties would be if they were rushing the assault on intact strongpoints, but it’s clear by now that this is not the case – Ukrainian reporters and soldiers who manage to evade censorship describe being pummeled by days on end of artillery before the Russians advance on them.

Russia will continue to grind the Ukrainians down with artillery, slowly but surely driving them from the Donbas. This is positional, attritional warfare, and it is allowing Russia to trade at absolutely absurd loss ratios. It is a simple transaction: Ukrainian manpower in exchange for time and Russian artillery shells. This is a trade that Russia will happily continue to make.

Slow Burn and the Economic Calculus

A methodical, firepower heavy approach in the east suits Russia for reasons above and beyond the brutal military logic. One of the more interesting aspects of the war has been the extent to which the economic and financial calculus have boomeranged in Russia’s favor. There are two aspects to this; one related to Ukraine, and one to Russia and the sanctions against her.

Let’s start with the Ukrainians, and more specifically let’s start by remembering that it was not Russia, but western agencies that predicted rapid Ukrainian collapse. Ironically, this was the low-cost scenario for the west. In the event of a quick Ukrainian defeat, the west would be left supporting an insurgency – as the Taliban demonstrated, this is a very cost effective way to harass and harm a great power. Instead, Ukraine stayed upright for the moment and is stuck fighting a costly war of attrition that it cannot win.

This is very important – instead of cheaply funding and arming an insurgency, helping coordinate acts of sabotage and the like (something western intelligence agencies excel at), the west (mostly the United States and to a lesser extent the UK) is stuck financing a hemorrhagic Ukrainian state and attempting to prop up its armies. This is far more costly than an insurgency, both in pure dollar amounts and in the level of munitions and equipment that are being poured into Ukraine.

Already, we have seen plenty of evidence that the attempt to supply Ukraine is draining western inventories. Smaller NATO members have already sent much of the capability in their limited arsenals, but even more alarming is the acknowledgment that American stockpiles are being depleted. Leaked texts have revealed that active duty units are being stripped of weaponry for shipment to Ukraine, while a recent Wall Street Journal article claimed that US stockpiles of howitzer ammunition are “uncomfortably low.”

Meanwhile, analysis from the Royal United Services Institute (a UK based defense thinktank) came to the sobering conclusion that manufacturing in the west is too degraded and too expensive to keep up in a war like the one being fought in Ukraine right now. A few highlights of that report:

- Annual American production of artillery shells is sufficient for only two weeks of combat in Ukraine.

- Annual Javelin anti-tank missile production is, at best, sufficient for 8 days of combat.

- Russia burned through four years worth of American missile production in the first three months of the war.

Russia so far has demonstrated that it can sustain its operations in Ukraine with ease; artillery activity in the east remains relentless (even with HIMARS systems hitting a few ammo dumps here and there), and the Russians have specially made a mockery of the relentless predictions that they are almost out of missiles. On Ukrainian Independence Day (August 24), the Russians launched the largest and most sustained missile attacks of the war, as if to deliberately mock those who predicted that the would be out of missiles by the start of summer.

In short, because Ukraine has little indigenous production and logistics, the west is bearing the actual industrial and financial burden of the war for them, and this burden is becoming far heavier than western planners expected. The logic of the proxy has been reversed; Ukraine has become a vampiric force, draining the west of equipment and munitions.

On the other side of the coin, the logic of sanctions rebounded strongly against the west. Western governments hoped that a rapid, all-in sanctions regime against Russia would crush the Russian economy and turn the Russian people against the war. The second part of this assumption was always silly – Russians blame the west, not Putin, for sanctions. Even more importantly, however, it is clear that Russia’s economic planning for this war bore tremendous fruit.

At the risk of massively oversimplifying the economics, the Eurasian vs Western economic rift that is emerging is a contest between a bloc that is rich in materials and a bloc rich in dollars. Attempts to financially strangulate Russia have so far failed, both due to the competence of Russia’s central bank, and due to the basic fact (which should be trivially obvious) that a county which makes its own energy, food, and weapons will always be difficult to pressure. The western sanctions regime was largely doomed from the start, because Europe simply cannot embargo the energy products that are the main source of Russian revenue.

Russia’s energy weapon remains the bomb in the heart of the EU. With all the “winter is coming” memes floating around, it can be easy to write this off as simply a figment of the internet. Far from it – small businesses around the EU are already closing in the face of crushing energy bills, energy intensive industrial sectors like smelting are shutting plants entirely. Europe is facing a perfect economic storm, as the Federal Reserve hikes rates, leading to a general tightening of financial conditions, energy prices explode into the stratosphere, and export markets dry up amid a global economic slowdown.

All of this is likely to tip over into a cataclysm over the winter. I would not be surprised to see a financial collapse and unemployment in the EU in excess of 30%. Given the fact that the EU is notoriously bad at solving problems of any kind, there’s a non-negligible chance more countries try to leave the EU. Spexit anyone?

Based purely on the economic trajectory, I believe Russia has absolutely no interest in ending the war this year. They are attriting Ukrainian manpower and dragging the EU to the precipice of the largest economic crisis since the Great Depression. America will be far better off, simply because it has its own indigenous energy supply and is generally wealthier and more robust than Europe in every way. But even if Americans won’t freeze and starve, contagion from European collapse promises economic difficulty for Americans already struggling under inflation. And in the end, because Ukraine is at this point completely dependent on the west for financial and material, a major economic blow to the west would also be catastrophic for the Ukrainian pseudo-state.

What Comes Next

My overall prognosis is very simple: I believe that Russia has degraded Ukraine’s military capabilities beyond repair, and is now doing the methodical work of grinding away the rest, while forcing the west to bear the unexpected burden of propping up the Ukrainian state and army.

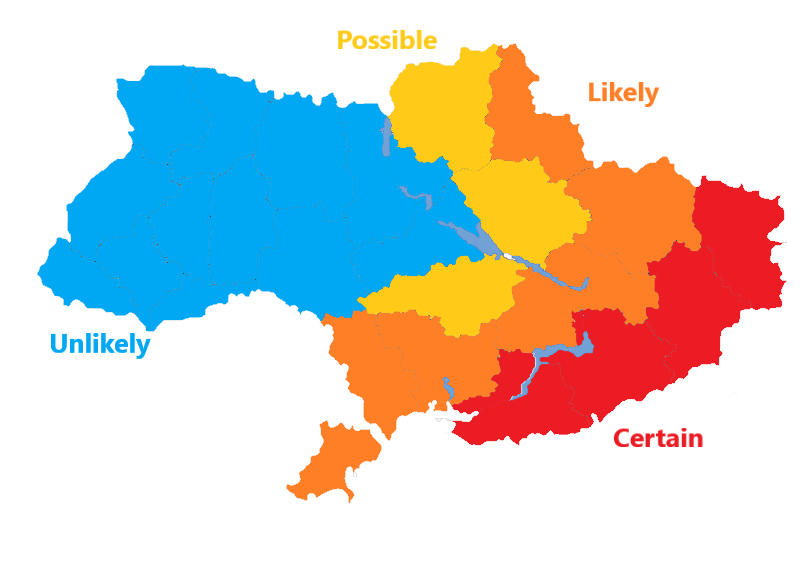

The actual intricacies of Russia’s operational plan of course remain a secret, but I believe there is a good chance that most of Ukraine east of the Dnieper will be annexed, as well as the entire Black Sea littoral.

At a certain point, two things will happen that will accelerated the pace of Russia’s gains. First, Ukrainian military capability will be attrited to the point where they can no longer effectively offer static defense, as they are doing now in the Donbas. Secondly, western support for Ukraine will begin to dry up, at which point Ukraine will be exposed as a failed state that cannot function independently.

I have voiced my opinion that Ukraine would launch some sort of counteroffensive at some point, simply because the political logic dictates it. Ukraine is under intense pressure to prove that it can retake territory; if it cannot, then this entire war is, at best, an attempt to force a stalemate of sorts and limit the extent of territorial losses. Western sponsorship demands that Ukraine retake territory, and as of this writing they are attempting to do just that around Kherson.

Ukraine simply has no hope of success waging a successful, full scale offensive. For one thing, offensive actions are hard. It’s difficult to successfully coordinate multi-brigade action – so far in Kherson, they are struggling to concentrate more than a battalion at critical points. Russia has combined armed reserves, artillery advantages, and a tremendous edge in airpower. Ukraine cannot achieve strategic objectives – all they can do is trade the lives of their men for temporary tactical successes that can be spun into wins by their propaganda arm.

The failure of the Kherson counteroffensive will accelerate progress towards the two tipping points, both by degrading the Ukrainian army further, and souring westerners on continuing to support Ukraine. Winter and the ensuing economic chaos will do the rest.

By Big Serge

Published by Big Serge Thoughts

Republished by The 21st Century

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of 21cir.com

Sharing is caring!